As the world transitions toward renewable energy, the challenge of storing excess power remains a critical hurdle. One innovative solution gaining traction is the concept of geothermal batteries—a system that leverages abandoned oil wells to store energy underground. This approach not only addresses the growing need for large-scale energy storage but also gives a second life to decommissioned fossil fuel infrastructure.

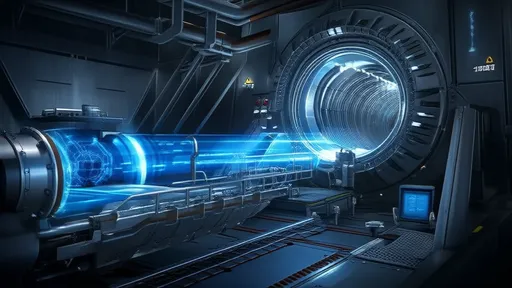

The idea is deceptively simple: excess electricity from wind or solar farms is used to heat water or other fluids, which are then injected into sealed, inactive oil wells. The surrounding rock acts as a natural insulator, preserving the heat for extended periods. When energy demand spikes, the hot fluid is pumped back to the surface, where it can generate steam to drive turbines or supply direct heating. Unlike conventional batteries that degrade over time, these geological reservoirs could theoretically store energy indefinitely with minimal losses.

Why abandoned oil wells? There are an estimated 2.6 million abandoned oil and gas wells in the U.S. alone, many of which pose environmental risks through methane leaks or groundwater contamination. Retrofitting them as thermal batteries would mitigate these hazards while creating value from dormant assets. The existing boreholes and subsurface knowledge from drilling operations significantly reduce exploration costs compared to digging new geothermal systems from scratch.

Recent pilot projects demonstrate the technology’s viability. In Texas, a consortium of energy companies successfully stored heat at 150°C in a depleted well for six weeks before extracting 75% of the energy—a efficiency rate competitive with lithium-ion batteries. Meanwhile, European researchers are experimenting with supercritical CO₂ as a heat-transfer fluid, which could improve energy density and reduce pumping costs in deeper wells.

The geological prerequisites aren’t overly restrictive. Wells need sufficient depth (typically 1,500+ meters) to reach temperatures that make heat storage practical, along with impermeable caprock to prevent fluid migration. Many former oil fields meet these criteria, especially those previously tapped for steam-assisted extraction. This makes regions like California’s Central Valley or Alberta’s oil sands prime candidates for early adoption.

Economic and environmental synergies set geothermal batteries apart. Unlike pumped hydro (the current grid-scale storage leader), these systems don’t require mountainous terrain or massive water supplies. They also avoid the mineral constraints and recycling challenges of chemical batteries. Perhaps most compelling is their ability to decarbonize industrial heat—a sector responsible for 20% of global emissions—by providing on-demand steam for factories or district heating networks.

Critics highlight valid challenges. Maintaining well integrity over decades of thermal cycling isn’t trivial, and mineral scaling could reduce efficiency. There’s also the question of whether oil companies—often reluctant to assume long-term liability for abandoned wells—would invest in retrofits without policy incentives. Still, with the U.S. Department of Energy now funding feasibility studies, the technology is moving beyond theoretical models.

Looking ahead, geothermal batteries could reshape energy geopolitics. Countries with extensive fossil fuel infrastructure—from the North Sea to the Middle East—might leverage these assets for renewable storage rather than abandoning them. For communities built around oil economies, it offers a pragmatic bridge to cleaner energy while preserving jobs and expertise. The Earth’s subsurface, once tapped for climate-warming fuels, may yet become one of our most powerful tools for stabilization.

As pilot projects scale up, watch for partnerships between geothermal startups and legacy oil firms. The marriage of drilling know-how with renewable innovation might just crack one of energy’s toughest nuts: how to store the sun’s rays and the wind’s whispers in the very scars left by the fossil fuel age.

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025