The field of aging research has witnessed a groundbreaking development with the emergence of partial reprogramming techniques, which promise to reset the biological clock of cells without erasing their identity. This revolutionary approach has sparked both excitement and caution within the scientific community, as researchers grapple with defining the safety boundaries of such interventions. The delicate balance between rejuvenation and potential risks remains a central focus as we explore the frontiers of longevity science.

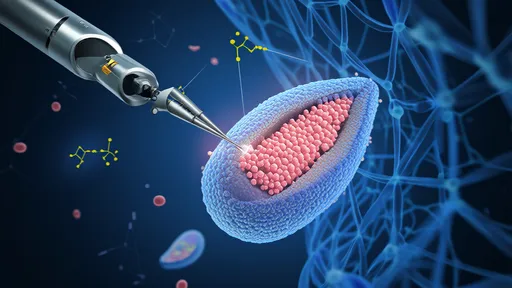

At the heart of this breakthrough lies the discovery that transient expression of Yamanaka factors – a set of four reprogramming genes (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) – can reverse age-related changes in cells without fully converting them back to a pluripotent state. Early experiments in animal models have demonstrated remarkable results, with aged mice showing improved organ function and extended healthspan following carefully controlled reprogramming protocols. These findings have opened new avenues for addressing age-related diseases, but they also raise important questions about the precise thresholds between therapeutic rejuvenation and unwanted cellular transformation.

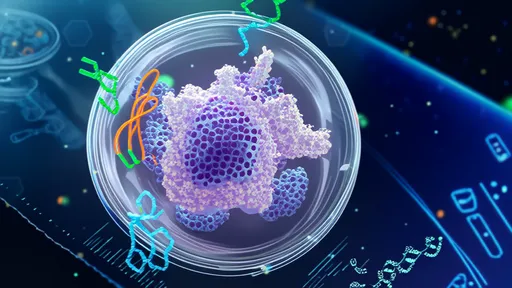

The concept of epigenetic reprogramming challenges our fundamental understanding of aging as a one-way process. Scientists have observed that aged cells accumulate epigenetic "noise" – chemical modifications to DNA that disrupt normal gene expression patterns. Partial reprogramming appears to clean this noise, restoring youthful gene activity profiles while maintaining the cell's specialized functions. This biological reset could potentially treat multiple aspects of aging simultaneously, offering advantages over conventional approaches that target single age-related pathways.

Safety concerns primarily revolve around the risk of incomplete reprogramming or unintended consequences such as tumor formation. The oncogene c-Myc, one of the Yamanaka factors, has particularly drawn scrutiny due to its known role in cancer development. Researchers are exploring various strategies to mitigate these risks, including shortened exposure times to reprogramming factors, alternative factor combinations, and pharmacological approaches that might mimic the rejuvenating effects without genetic manipulation. Recent studies suggest that precise temporal control of reprogramming factor expression may be key to establishing a therapeutic window where rejuvenation occurs without loss of cellular identity.

Another critical safety consideration involves tissue-specific responses to reprogramming stimuli. Different cell types appear to have varying thresholds for reprogramming, with some tissues being more susceptible to complete dedifferentiation than others. This heterogeneity presents both challenges and opportunities – while it complicates the development of universal protocols, it may allow for targeted approaches that address specific age-related conditions. The emerging field of single-cell analysis is proving invaluable in mapping these differential responses across tissues and cell populations.

The immune system's role in partial reprogramming adds another layer of complexity to safety assessments. Aging is accompanied by immunosenescence – the gradual deterioration of immune function – which could influence how the body responds to reprogrammed cells. Some researchers speculate that partial reprogramming might rejuvenate immune cells themselves, potentially creating a positive feedback loop that enhances the therapy's effectiveness. However, the possibility of immune rejection or autoimmune reactions to epigenetically altered cells remains a concern that requires thorough investigation.

Biomarkers of safe and effective reprogramming represent an active area of research. Scientists are working to identify molecular signatures that distinguish beneficial rejuvenation from potentially harmful dedifferentiation. These may include specific patterns of DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility changes, or metabolic shifts that correlate with successful outcomes in preclinical models. The establishment of such biomarkers would provide much-needed guidance for translating partial reprogramming from laboratory studies to clinical applications.

Ethical considerations accompany these scientific advancements, particularly regarding the appropriate use of age-reversal technologies. While the primary focus remains on treating age-related diseases, the potential for broader applications raises questions about societal impacts and equitable access. The scientific community emphasizes the importance of maintaining clear boundaries between legitimate medical research and premature commercialization of unproven anti-aging interventions.

Looking ahead, researchers are developing next-generation reprogramming approaches that may offer greater safety and precision. These include small molecule cocktails that could induce similar rejuvenation effects without genetic modification, and tissue-specific delivery systems that limit reprogramming to targeted organs. The integration of partial reprogramming with other longevity interventions, such as senolytics or mTOR inhibitors, may also yield synergistic benefits while allowing for lower, safer doses of each component.

The road to clinical translation will require rigorous testing in relevant animal models and eventually human trials. Several biotechnology companies have already initiated programs to develop partial reprogramming therapies, with initial targets likely including age-related conditions where current treatments are inadequate. As this field progresses, international collaborations are forming to establish standards and guidelines for the safe development of cellular rejuvenation technologies.

While the promise of resetting the aging clock is undeniably exciting, the scientific community remains cautiously optimistic. The coming years will be crucial for determining whether partial reprogramming can deliver on its potential to extend human healthspan without compromising safety. As research continues to define the boundaries of this technology, we may be witnessing the dawn of a new era in medicine – one where aging itself becomes a modifiable biological process.

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025